by Avi Schild

Itri Ruins in the Adulam Reserve: Susannah and I have hiked up to the site many times. Each time, I feel as if I am being invited to travel back in time and witness the life lived by its ancient inhabitants.

I remember my first time seeing the ruins. We came upon them with no expectations, then walked towards beautiful views, homes pulled up from the depths of the earth, and ritual baths and wine presses that looked as if they were just waiting for someone to use them again.

Standing there, we realized that this was yet another reason that we loved hiking in this country. It was that moment of connection: when catapulted back millenia, we stand in the same spot, see the same views, and experience the land as our ancestors and predecessors once did.

I believe that people cherish moments of connection like that and want to deepen them. I certainly do, and I found myself wondering about the ruins and the people who lived there. Who were they? How did they live their lives? What was their ultimate fate?

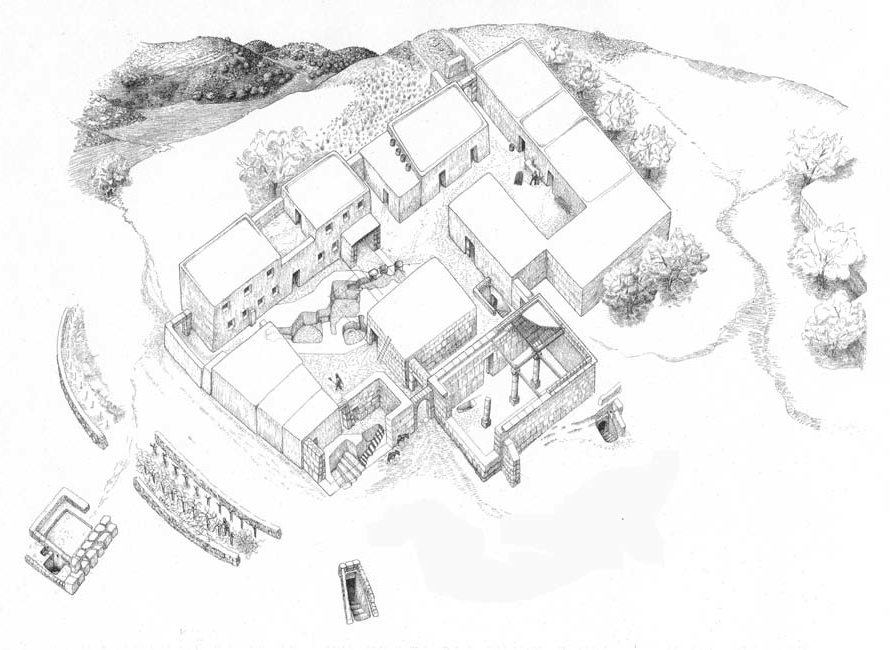

There is a sign at the site that gives only the briefest account of the village. The ruins we see are from the Second Temple period, and the village stood until the Bar Kochva revolt. The inhabitants were Jewish, and the collection of wine presses at the site gives us a unique perspective on the ancient farmer life. The sign includes a beautiful artist’s impression of how the village may have looked long ago.

Intrigued, I decided to dig a little deeper and see what I could find out about this village.

The Shfela or Judean Foothills

The site is located in an area which is today called the Adullam Grove Nature Reserve. The Adullam area is rich with history. An archaeologically inclined adventurer could easily lose himself in the many ruins and their ancient Biblical descriptions.

The nature reserve itself is located in the Judean Foothills. The Judean Foothills serve as a transition between the coast to the west and the Judean Mountains (including Jerusalem) to the east. Over the course of 15 kilometers, the area rises from about 20 meters above sea level to 460 meters above sea level. Beyond the foothills, the Judean Mountains continue to rise to over 1000 meters above sea level.

When the Israelites settled in the land, the Philistines were living along the coast. During that time, the Shfela (Judean Foothills) was the main point of contact and friction with the Judean Mountain Israelites. Famous battles occurred in the area, like those described in the story of David and Goliath and stories of the warrior Samson.

There are five main valleys that bisect the Shfela and lead from the coastal plains to the mountains: the Ayalon Valley, the Sorek Valley, the Elah Valley, the Guvrin Valley and the Lachish Valley. Fortified cities were built on opposing sides of these valleys by the Israelite and Philistine nations to protect passage. The city of Adullam was one such city, overlooking and protecting the Elah Valley. Many villages were built around the fortified cities to take advantage of the rich soil. Itri was one of those villages, sitting on a hilltop 406 meters above sea level. That’s where our story begins.

Back to the Beginning

Most of the research at the site was done by Boaz Zissu of Bar Ilan University and Amir Ganor of the Israel Antiquities Authority. What the researchers found points to almost 800 years of history, from the 4th century BCE to the 5th century CE. That seemed like a long history to me, and I was eager to understand what they found that led them to that conclusion.

The story of Itri is really a Second Temple story. Researchers believe that Itri was initially built in the 4th century BCE – let’s say around 350 BCE. What was going on then? About 250 years earlier, the Babylonian Empire had decimated the Kingdom of Judah, the city of Jerusalem and the First Temple. Most of the inhabitants had been displaced to Babylon or Egypt.

Shortly thereafter, the Persian king Cyrus the Great defeated the Bablylonians, and allowed displaced peoples to return to their lands and worship their gods. This led to the building of the Second Temple in Jerusalem within an area called Yehud Medinata. Yehud Medinata was a Persian province that was self-governed by the Jews who returned to Israel. Zerubbabel, Ezra and Nehemiah were some famous governors of Yehud Medinata.

Sometime around 350 BCE, the Jews in this self-governing province were given permission to mint their own coins. These coins are today referred to as Yehud coins, and a few of them were found in the Itri ruins. These finds, along with pottery that dates back to the Persian Empire, allows scholars to date the builders and first inhabitants of Itri to that time period. The presence of a coin minted in Babylon may indicate that the initial inhabitants included Jews from the Babylonian exile who returned to Israel with the Cyrus declaration.

Hellenistic Period

Towards the end of a two hundred year period of peace for the Jews in Yehud Medinata, Itri was built. Shortly afterwards, around the year 332 BCE, Alexander the Great conquered Judea and it became part of the Greek kingdom of Macedon. The empire splintered after Alexander’s death. Judea found itself in a power struggle between two of those splinter kingdoms: the Ptolemaic and the Seleucid Kingdoms. It was the actions of one of the Seleucid kings, Antiochus, that led to the story of Hanukkah and to the rise of the Hasmonean Dynasty from 165 BCE to 37 BCE.

We don’t know what role, if any, Itri played in these events. Besides the actual remains of walls, cisterns, and quarries at Itri from this time period, many coins minted by the various powers were also found. This includes bronze coins of both the Ptolemaic and the Seleucids along with hundreds of prutot of various Hasmonean kings.

The last years of the Hasmonean Dynasty were marked by internal fighting and conflict. This conflict led to Jerusalem being conquered by Rome in 63 BCE and the beginning of the Roman period of Judea. The Hasmonean kings became clients of Rome for another 27 years until Herod the Great was proclaimed King of the Jews by Rome. His rule and the rule of his sons lasted about 44 years until 6 CE.

Early Roman Period

The 1st and 2nd century CE were tumultuous times in Judea, which ultimately led to the destruction of the Temple and the killing or banishment of virtually all the Jews in the area. Itri was part of these events and its inhabitants shared the same fate.

During the first half of the 1st century CE, the village expanded to its largest size, about 10 dunam or two and a half acres. The village had two central plazas, which led to smaller lanes bordered by simple homes (really just rooms) with courtyards. The roofs were made of wooden beams with branches and soil on top. Rainwater was channeled off the roofs, down pathways into twelve water cisterns and four mikvaot (ritual baths). Beneath some of the homes, small tunnels were built as storage chambers.

The village was primarily agricultural, with wine presses cut into the rock and olive presses to make oil. Written evidence found at the site suggests that the village traded in dried figs. The columbarium unearthed there suggests they raised pigeons. Other discoveries tell us that they spun and wove textiles.

As Judea moved into the second half of the 1st century CE, mounting tensions within and without led to an outbreak of the Great Jewish Revolt against Rome in 66 CE. Fighting was fierce, but still resulted in the destruction of the Second Temple, Jerusalem, and other rebel fortresses like Massada.

Two powerful finds from this period drive home how real this was for the residents of Itri. The first is the coins dated to the second and third year of the war. Specifically, one coin was found with the words Half Shekel (חצי השקל) and year 3 (שג) on the front and Jerusalem the Holy (ירושלים הקדושה) on the back. These coins were minted as a way to emphasize independence from Rome.

The second find was a burnt layer and ashes in some of the buildings. The village had been at least partially destroyed by the Romans and subsequently abandoned for a short time.

Between the Great Revolts

The Jews of Judea mounted another great rebellion against the Romans in 132 CE called the Bar Kokhba Revolt. Sometime between the two revolts, Jews resettled the village. Scholars estimate that during this time the settlement was less than half the size it had been before it was destroyed. It was during this time that the residents started building underground tunnels and rooms.

The Roman historian, Cassius Dio, who lived in the years after the Bar Kokba Revolt, reports:

“To be sure, they did not dare try conclusions with the Romans in the open field, but they occupied the advantageous positions in the country and strengthened them with mines and walls, in order that they might have places of refuge whenever they should be hard pressed, and might meet together unobserved under ground; and they pierced these subterranean passages from above at intervals to let in air and light. (Historia Romana, LXIX, 12, 3).”

Archeaologists found coins minted by the rebels amongst the ruins. Some of them bore the inscriptions “For the freedom of Jerusalem” and “Year Two of the Freedom of Israel.”

Ultimately, the rebellion was crushed and Judea was destroyed. As written by Cassius Dio:

“Fifty of their most important outposts and nine hundred and eighty-five of their most famous villages were razed to the ground. Five hundred and eighty thousand men were slain in the various raids and battles, and the number of those that perished by famine, disease and fire was past finding out. Thus, nearly the whole of Judaea was made desolate, a result of which the people had had forewarning before the war.”

Itri was no exception. The village was burned, as is evidenced by another burn layer and burn marks on some of the coins found. More troublesome was what diggers found in one of the ritual baths: the Mikvah had been used as a mass burial and contained the skulls and bones of at least twelve people, including 7 adults, 4 adolescents and one fetus. One of the adults had been beheaded by a sword

Around 200 CE, the village entered its final stages of habitation, with its first non-Judean residents. The new residents were likely Romans, perhaps even veterans of the Roman army who had been granted local estates. This phase of settlement lasted about 250 years, into the 5th century. Then Itri was abandoned for good. Over 1500 years elapsed before modern day Israeli researchers discovered that looters were active at the site. Israel decided to uncover the past and bring Itri’s history into the light.

These ruins emerged from the ground to tell the story of a small village swept up in some of the most profound experiences in Jewish History. From its position amongst the hills of the Shefela, Itri saw the return to Zion before the Second Temple, peace, war, rebellion, persecution, civil war, and ultimately death and destruction. This small site gives us the chance to relive our history, immerse ourselves in the stories of the places we came from. Perhaps most importantly, it allows us to reconnect with ancestors that have walked this Land before us.

Visit this site on a hike in Adulam described in this post.

Thank you to Boaz Zissu for his permission to use the artist’s sketch used to illustrate what the village may have looked like. That sketch was originally included in his article, Horvat ‘Ethri—A Jewish Village from the Second Temple Period and the Bar Kokhba Revolt in the Judean Foothills, appearing in the Journal of Jewish Studies, VOL. LX, NO. 1, SPRING 2009.

Incredible, this one has definitely been on my list for a while. Hopefully will make it out there soon.

Avi, thanks for your comprehnensive description of Itri’s history. I hope to see you in the near future on a tiyul!

Thank you for this very clear history of the site.

How long a hike is it? Where does one park?